Why is printing money a bad idea?

Mike MunayShare

A perfect plan

At first glance, printing money seems like a brilliant idea. If a country is in debt, poverty, or crisis... why not print more banknotes and distribute them? After all, the central bank has printers, right? It's a quick, visible, and tempting solution, especially in contexts of emergency or populism.

For many people, this sounds logical: if there's not enough money, create more, and that's it. But here's the trick: money isn't valuable because it's pretty or brightly colored. It's valuable because it represents a portion of a country's real wealth : its production, its resources, its capacity to generate goods and services.

Printing more money without more wealth behind it is like constantly inflating a balloon: it eventually explodes. And the worst part is that this trap isn't theoretical. We're not talking about a "what if..." scenario; we're talking about numerous cases throughout history of countries that have fallen into exactly this temptation: they've turned on the printer as if there were no consequences… and have ended up digging their own economic graves. They've literally printed their way to collapse .

The unstoppable crisis

When a country decides to print money to "create wealth," it's actually inflating the amount of banknotes in circulation without increasing the available goods and services . In other words, there's more money, but the same amount of things to buy . And that, in economics, is an explosive combination.

In the short term, it may seem like a brilliant solution: debts are paid, projects are financed, budget gaps are plugged, and perhaps even some social aid is distributed. Everyone applauds. It seems like magic. But it's just that: a momentary illusion . Because very soon, the market begins to realize the trick.

Imagine the economy is an 8-slice pizza. If you print twice as many bills, you're not making the pizza bigger. You're just cutting those 8 slices into 16 thinner ones. The result? Each slice is worth less. And if you were hungry... tough luck, because now people have twice as much money to buy the same amount of pizza. What does the pizza maker do? He raises the prices , of course. Because if there's more demand but the same supply, he charges more for each slice. Basic.

This widespread increase in prices is called inflation , and when it gets out of control, its savage cousin enters the scene: hyperinflation . This is where the country falls into a vicious cycle : since money no longer lasts, more is printed. But the more is printed, the more the currency is devalued . And the more it devalues, the more must be printed . And so on, in a loop, until the bills are no longer even good enough to wrap the pizza you can no longer buy.

In other words: printing money doesn't create value ; it just distributes the same value across more paper. And when that happens, purchasing power melts like cheese in a wood-fired oven. You're poorer, but with more bills in your wallet.

The problem outside

And as if what happens within the country weren't enough, things get even more complicated when we talk about international trade.

Because when your currency is devalued due to inflation or hyperinflation, the exchange rate against other currencies plummets . What does this mean?

- Buying products from abroad becomes extremely expensive. Importing technology, fuel, medicines, or basic foodstuffs can become almost impossible.

- And in the other direction, selling abroad also becomes a problem: even if your products are cheaper, the instability of your currency scares off buyers . No one wants to close a deal today and discover tomorrow that the money they received is no longer worth anything.

In short: hyperinflation not only affects your internal economy, it also isolates you commercially from the world , makes you dependent, and reduces your international bargaining power to that of a shipwrecked person pleading for help with a napkin.

So… where should the money come from?

The short answer: real growth .

The long answer: by producing more , by generating more value, by having a healthy economy that creates jobs, innovates, exports, attracts investment, and improves productivity. In other words, by making the pizza grow , not by cutting it into thinner slices.

When a country produces more goods and services—when it builds, invents, educates, sells, transforms, digitizes, and undertakes—it generates real wealth . And that wealth can support the creation of more money. Then you can print a little more, because you're generating the equivalent in economic value. It's like adding ingredients to a pizza before serving it : more dough, more cheese, more pepperoni… and then it makes sense to serve more slices.

The opposite, printing banknotes without that productive backing, is like cheating in a game of Monopoly. You think you're the king of the strip, you hand out banknotes left and right, you build hotels everywhere... but only on the board. In real life, no one will accept those banknotes, no one wants your plastic hotels, and when the game is over, it all goes back into the till.

Therefore, healthy money isn't the kind that's printed, but the kind that's generated . Money that comes from a functioning economic system, not from a desperate printer.

So why is money printed?

Good question. Because after all this, one might think: "If it's so clear that printing money causes problems... why do some countries continue to do it?" The answer, like almost everything in economics, is: it depends . Because yes, there are ways of printing money that make sense. And others that are downright a display of ignorance, improvisation, and economic mediocrity .

✅ When printing money makes sense

Printing money isn't always bad . In fact, all countries do it in a controlled manner. For example:

- To replace old, damaged or out-of-circulation banknotes .

- To technically adjust the monetary base , based on real economic growth, consumption and other indicators.

- In specific and planned situations, as part of expansionary monetary policies carried out by independent and sensible central banks (yes, they still exist, at least sane enough not to print money like crazy).

In these cases, wealth is not being created out of thin air, but rather maintaining the balance of the financial system .

❌ When printing money is nonsense

The problem arises when money is printed because no one knows how to do anything else . Literally. Because governing an economy is difficult, of course. It requires boosting productivity, attracting investment, promoting innovation, managing resources, reforming structures, boosting education, and, in general, thinking long-term .

But of course, that's a chore. And when there's no vision, there's plenty of paper. Then we fall into the temptation of the easy way out: printing bills to pay public salaries, plugging loopholes, feeding unsupported subsidies, or simply giving the impression that something is being done .

The root of the problem? In many cases, it's as simple as this: the decision-maker doesn't understand how the economy works . Or worse: they understand, but choose the short-term option that yields immediate political benefits. And in both cases, the country pays dearly. Very dearly.

Printing unbacked money isn't economic policy: it's an act of desperation disguised as initiative . And behind that desperation is often mediocre leadership, incapable of creating real and sustained wealth.

The most brutal hyperinflations in history (due to overdoing it with the printer)

1. Zimbabwe (2007-2009): When a banknote wasn't even good enough to go to the bathroom

Zimbabwe became the global meme for hyperinflation. The trigger? A series of catastrophic economic policies, coupled with the decision to print money uncontrollably to finance public spending .

- Annual inflation rate in 2008: 89,700,000,000,000,000,000,000 % (yes, that's 89.7 trillion percent).

- The government's solution? Print 100 trillion Zimbabwean dollar bills.

- What could you buy with that? Maybe a loaf of bread... if you hurried.

In the end, the currency collapsed and the country had to dollarize its economy to survive.

2. Germany (1921-1923): when a cart of banknotes was worth less than the cart

After World War I, Germany was up to its neck in debt. What did they do? The same old thing: print money to pay reparations and debts . The result? Inflation so absurd it seems fabricated.

- In November 1923, 1 US dollar was worth 4.2 trillion German marks .

- People were paid twice a day to spend it before it lost value.

- There were those who burned banknotes to cook or heat their homes : it was cheaper than buying firewood.

The effects of this economic crisis created a social and political breeding ground that, over time, would tragically change the history of Europe.

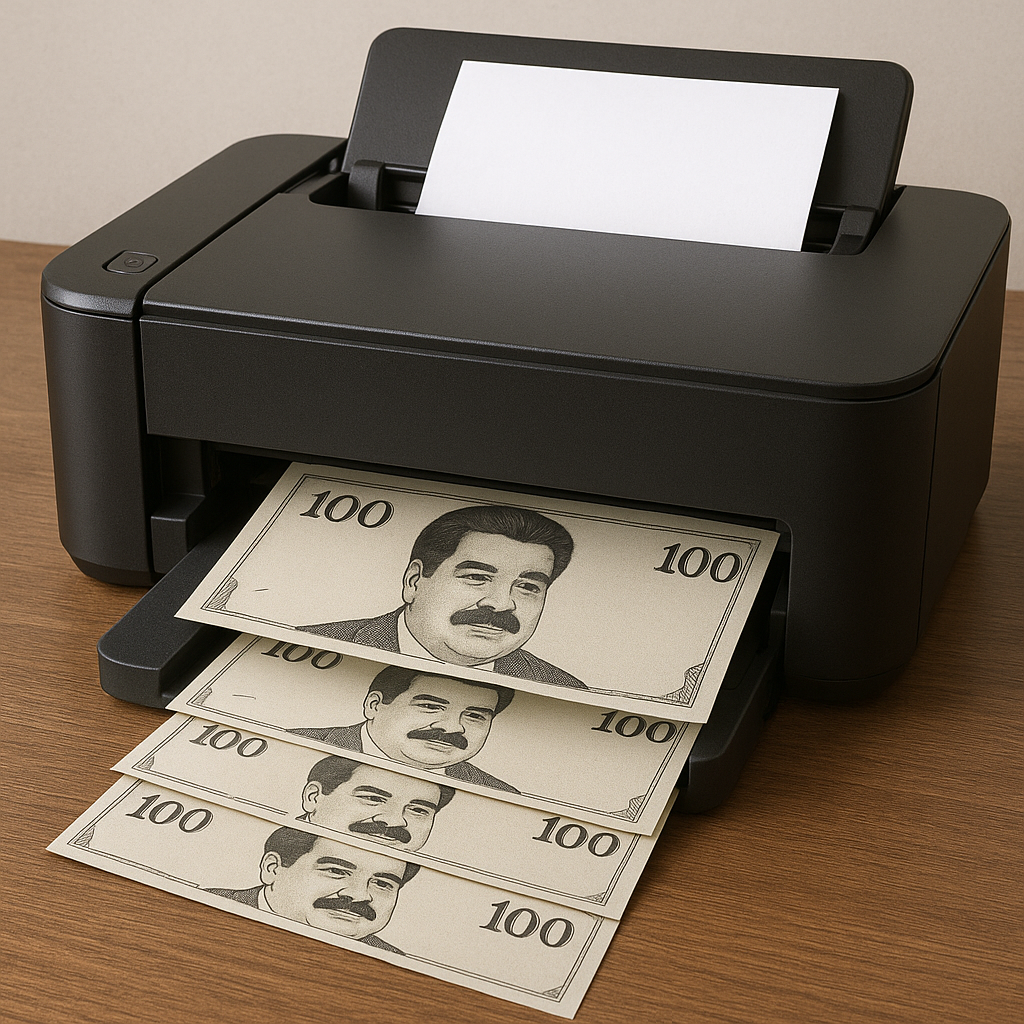

3. Venezuela (2016 onwards): oil, paper and skyrocketing prices

Venezuela, with one of the world's largest oil reserves, has plunged into a brutal crisis. The cause? A mix of corruption, economic mismanagement, and, of course, uncontrolled money printing to finance public spending .

- In 2018, annual inflation exceeded 1,000,000% .

- New banknotes entered circulation every few months, and they were worth less than toilet paper .

- Businesses stopped accepting bolivars, and people migrated to dollars, bartering, or cryptocurrencies.

The Venezuelan economy remains broken, and confidence in its currency is practically nonexistent, making it difficult to see whether this will be resolved in the long term.

4. Argentina (several times): the déjà vu of inflation

Argentina hasn't had just one hyperinflation. It's had several. In fact, it could be a candidate for the inflation Olympics, because it's been training for decades. Since 1975, the country has been on an economic roller coaster marked by uncontrolled currency printing , fiscal crises, devaluations, and currency exchanges like T-shirts.

Everything began to seriously spiral out of control in 1975, with the so-called "Rodrigazo," a brutal devaluation that sent inflation soaring to 335% annually . It marked the beginning of a long era of instability. Since then:

- In 1983 , when democracy returned, inflation was already above 300% per year .

- In 1985 , a new currency, the austral , was launched to replace the Argentine peso. Spoiler alert: it didn't work.

- In 1989 , hyperinflation truly hit: inflation exceeded 3,000% annually .

- In supermarkets, employees would mark up prices several times a day , and people would rush out to spend their pay before it lost value in a matter of hours .

A fact that perfectly sums up the madness: at that time, there was a myth (not so much a myth) that some merchants weighed the bills instead of counting them , because it was faster than adding up zeros.

Then came the current peso (converted at 1 to 10,000 against the austral), convertibility with the dollar in the 1990s, the corralito, the 2001 crisis, and so on. In recent years, the cycle has repeated itself: fiscal deficit + issuance = inflation + devaluation . A familiar recipe, but nonetheless, despite its age, it works… badly.

To see the magnitude of the problem, a recent fact suffices:

- In 2015 , 1 euro was worth about 10 Argentine pesos .

- In 2025 , 1 euro will be worth more than 1,100 pesos .

If you exchanged 1 million euros for pesos (10 million pesos) in 2015, those same pesos are only enough to buy back about 9,000 euros today. Ninety-nine percent of the value has vanished into thin air.

The Argentine case is a perfect example of how failure to learn from mistakes can turn a cyclical crisis into a way of economic life.

Final insight: paper can handle anything, the economy can't.

Printing money without control is, in essence, a declaration of incompetence . It's what you do when you don't know how or don't want to do the hard work: building a functioning economy. It's like trying to fix a leak with duct tape: it seems like it fixes something, but it ends up blowing everything up .

Zimbabwe did it. Venezuela did it. Germany did it. Argentina did it. And all of them, without exception, have proven the same thing: there's no shortcut to riches other than printing . You can fool people for a while. You can plug holes. You can play the magician. But economics, like physics, doesn't deal in fantasy .

Money isn't wealth. It's a reflection of it. It's the trust we place in that piece of paper that's worth something because it's backed by work, production, innovation, education, and solid institutions. When you print without backing, all you produce is paper and mistrust .

And when trust is lost, there is no bill, no decree, no speech that can restore it.

So, the next time you hear someone say, "What if we print more money?" show them a graph. Or a pizza. But above all, remind them that countries aren't built on ink, but on ideas. And the courage to implement them.

#micdrop